They say it does not take much to start a debate among the "bhodroloks" of West Bengal. Just ask which football team they support -- Mohun Bagan or East Bengal.

However, if the BJP has its way, then this sporting rivalry – teams populated mostly by people from different sides of the divisions that came after the British Partition of Bengal in 1905 – may soon spill over into the political arena.

What's worse, this could also lead to deep religious rifts in a state that – some claim – is already divided over religious issues, especially under the rule of the Trinamool Congress and chief Mamata Banerjee.

The history

The British had divided Bengal along religious lines in 1905, with most of what is present-day Bangladesh becoming East Bengal. That was the Muslim-majority side. West Bengal was the Hindu-majority side.

The British had then left India with another wound, in the form of the Partition of 1947. What was East Bengal had become East Pakistan, and state lines became national borders. Unperceived by the human eye, a different border was also etched along this physical one: the one that separated religions.

As part of Pakistan, the people of East Pakistan expected prosperity. However, while West Pakistan – present-day Pakistan – beggared it by using its surpluses, the people were fed populist moves like the establishment of the National Assembly of Pakistan in Dhaka.

As the demand for Bengali nationalism in East Pakistan increased over time, so did political repression. When Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – recognised as the founding father of the People's Republic of Bangladesh – was not allowed to take office as the prime minister of Pakistan despite his party winning 167 of the 169 seats in the National Assembly in 1970, those chants for a separate country received a massive push.

That Bengali literature – including that of late Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore – had been banned in Pakistan by then only served to bring matters to a head.

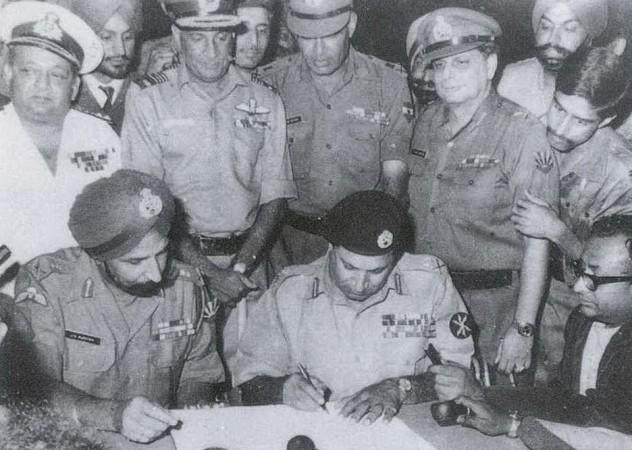

The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 – where the people of East Pakistan received some help from India – managed to get the country out of the clutches of Pakistan. However, Bangladesh was still a Muslim-majority country, while most Hindu Bengalis were in West Bengal.

Paling similarities

West Bengal and Bangladesh still have a lot in common, not the least of which is language. Bangladesh also uses a composition by Tagore as its national anthem, making the litterateur the only person in the world who has written the national anthem of two countries – India being the obvious other.

The people from both sides of the border also share a liking for certain food items, like fish. However, this is where the dissimilarities – which may devolve into rivalries – start to kick in. Ghotis – people who were originally from West Bengal – sing paeans to lobsters: Chingri Machher Malaikari has no rival. Bangals – people originally from what is now Bangladesh – however, like to vaunt the hilsa.

While hilsa is a favourite on the Indian side as well, but a true-blue Ghoti will look at it with the same disdain as a Bangal would look at some succulent prawn/lobster curry made with coconuts, all the while drooling internally.

And then, of course, there is the shared love of football that comes with an equal measure of arch-rivalry whenever there is a Mohun-Bagan-versus-East-Bengal debate.

Such a sporting rivalry often spills over onto social media, with trolls abandoning sporting merits to deride their opponents over either their intelligence or dialect or the fact that they crossed the border – whether willingly or unwillingly – and left behind a country that they had initially chosen to live in.

Religious overtones

With BJP national president Amit Shah announcing that the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which is being implemented in Assam, may also come to Bengal, the door is now wide open for religious hostilities to begin.

Sure, the Ghoti versus Bangal hostility was there, but only among Hindus. However, under current West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee's regime, there are accusations that the ruling Trinamool Congress has catered to the whims of a single minority community almost singularly.

Incidents such as the common Bengali words for father and mother – "Baba" and "Ma" – being replaced by the Urdu-leaning "Abba" and "Amma" in school textbooks prescribed by the state government have only fanned the aforementioned allegations.

If the NRC is implemented in West Bengal, it will definitely lead to polarisation along religious lines, and the BJP will leave no stone unturned to blame any resulting violence and unrest on Banerjee and her policies. After all, Shah has already started asking why Banerjee is "protecting" people coming into the state illegally from Bangladesh.

[The author currently teaches at St Joseph's College (Autonomous), Bengaluru. The views expressed are his own.]