Bad mergers create bad blood – in the skies and on the ground. When the government merged India's two state-owned airlines in 2007, Air India and domestic carrier Indian Airlines, the combined entity would soon grow into a megalith symbolising all the shortcomings of India's public sector.

In just a generation, competition from the private sector, rising fuel costs as a percentage of operational expenditure, strikes by opposing factions of pilots, freebies and upgrades to politicians and bureaucrats, and huge discounting would move the Maharaja from monopolising air travel to being only India's third largest airline with a 11.8 percent market share.

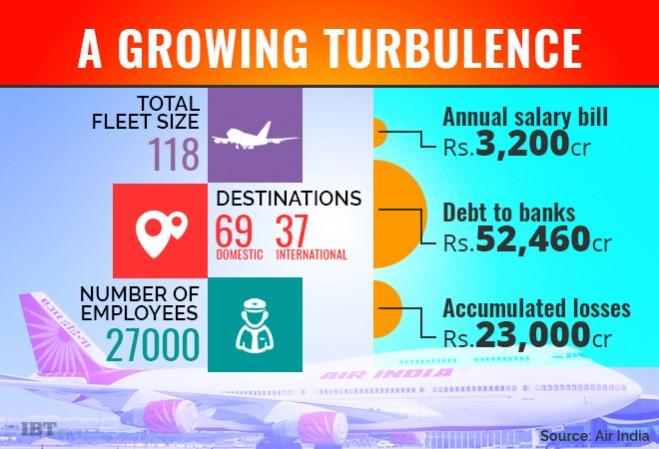

But the literal bottomline here is: Air India has lost money almost every year since its merger despite the UPA II government infusing Rs 30,000 crore into Air India under a financial restructuring plan (FRP). Total equity infused in the airline thus far is Rs 22,280 crore. Banks currently have an exposure of about Rs 53,980 crore.

A diverting fact is that state-owned Air India utilised government bailouts while launching price wars with other airlines as part of its survival requirements, leading to the logical conclusion that the government was helping subsidise monopolistic behaviour.

Another FRP by the present BJP dispensation to infuse Rs 42,182 crore as additional equity over 22 years has been delayed as the airline grapples with the problem of handling over Rs 50,000 crore in debt, of which an estimated Rs 23,000 crore is by way of aircraft loan advances. It is a no-win situation exacerbated by the airline's asset deterioration down the years and its inability to even control its operating losses since 2011.

Last year, for the first time in about a decade, Air India managed to post Rs 105 crore in operating profit (net loss after tax in 2016 -- Rs 3,836.77 crore) on the back of fresh capital infusion from the government and lower ATF prices. But was the intangible benefits of holding on to a 13 percent market share worth splattering more red ink on a battered balance-sheet? The government didn't think so. Its decision to divest the national carrier spoke of the triumph of experience over, often unrealistic, hope.

Dreams Un-lined

The national career was a symbol of public sector ingenuity and operational inventiveness down the decades till its much- ballyhooed merger with Indian Airlines. Then, the losses started piling up with fresh competition from the private sector on key sectors within India. Even Vijay Mallya's doomed Kingfisher took valuable market share away from Air India. Middle East carriers like Emirates, Gulf Air and Qatar Airways gained top-of-the-mind recall for expatriate travellers to destinations like Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Jeddah and Muscat.

For a government long in denial about the dismal picture which Air India presented, the benefits of disinvesting the airline in a single swoop are far more than taking a piecemeal approach as recommended by critics who suggest that it retain 51 percent in the asset-heavy airline. Air India owns prime land in cities like Mumbai, Chennai and Kolkata, the sale of which, disinvestment supporters expect will vault the airline out of troubled times. But this asset class, going by the airline's own assessment, would yield only Rs 10,000 crore which is not a scratch on its huge debt burden.

The Dreamliner aircraft and its entitled pilot crews have remained a thorn in the airline's flesh to this day. Pilot strikes and mutinies since 2012 and largescale operational mismanagement took the airlines to a new low. The airline incurred operational losses of Rs 5,537 crore in 2012 (or Rs 15 crore every day). Subsequent years were not too different, though going by the government's claims, Air India was actually paring down its losses fiscal after fiscal.

Minister of State for Civil Aviation Jayant Sinha had exuded confidence about the airline's performance since last year, and earlier this year, asserted that it would show operating profits of Rs 300 crore in 2016-17, and the government had no plans to privatise the airline – till the latter poured cold water over his enthusiasm by announcing that a disinvestment program to sell the airline and recover its losses would soon be underway.

The Comptroller & Auditor General (CAG) made things stickier when it said that the airline had actually posted operating losses of Rs 321.40 crore in the April-June period of 2015-16, when the government had claimed a profit.

But Air India said that its operational performance targets were in line with the turnaround plan. A spokesperson said that "considerable improvement" in on-time performance at 78.2 percent was achieved in 2015-16 as compared to 68.2 percent in 2011-12. The available evidence didn't justify the airline's claims.

Taking the debt-free road

The logical answer to Air India's problems is privatisation — but politicians and bureaucrats, who misuse India's flag carrier as much as its employees do --, would baulk at such a move. Air India has been surviving on the Rs 30,000-crore bailout package put together by UPA-II in 2012 to help its turnaround, as well as debt relief provided by public sector banks. It is estimated that even a well executed asset sale may not fully cover the airline's liabilities, and taxpayers cannot escape footing part of the loss — either directly in case the government pays off the airline's creditors, or indirectly if the public sector banks write off their loans to the airline.

The three options on the table could be a full 100 percent selloff, a 74 percent stake sale or retaining a 49 percent share in the airline, as per a tentative note from the Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM).

The decision to form an Air India-specific Alternative Mechanism to take forward the disinvestment plan is timely. But this Mechanism should first shed clarity on how the eventual sale will be executed -- whether the airline will be fully privatised or hived off asset-wise to interested bidders like IndiGo, which has expressed interest in buying out the carrier's international operations and peak hour landing slots in airports like London and New York. These slots if sold should fetch the government at least Rs 3,000 crore.

A sale of market slots in airports like Delhi and Mumbai would be attractive to foreign airlines to invest in India, though the government's stakeholding and quantum of divestment will come under their scrutiny before entering the bidding fray. Experts have suggested that the value of the heritage Air India brand can't be overlooked either, when even Kingfisher's hostile lenders valued that brand at Rs 160 crore.

If both foreign and prospective domestic buyers like Indigo, are allowed to bid freely for the airline, more value could be realised from a sale. There have been suggestions to add more value to the airline's assets by hiving off non-core assets with high profit potential into a shell company and demerger and strategic disinvestment of profit-making subsidiaries. This make sense only if the government considers making key changes in its FDI policy to allow foreign investors to buy a more substantial stake in Air India. If it is possible to invest 74 percent FDI in telecom, then why not in aviation?

The highly rated Tata-Air Asia Berhad JV which saw Air Asia grabbing a foothold in the huge Indian market, has still not fulfilled its initial promise. Going by the record, almost all airlines that have lost money have only themselves to blame. Their painpoints include inefficient operations, aggressive expansion without consolidation, balance-sheets which are leveraged unduly high, improper route planning and wrong pricing of tickets. These factors have contributed more to the downfall of many an airline meeting its Waterloo in the Indian aviation market, rather than the market itself -- which is growing and has many milestones ahead of it. Carriers like IndiGo have excelled in the same market. Stabilising Air India will be an important step ahead for Indian aviation. For a start, in the event of a successful sale, the government and its ministries must start seeing Air India as a revenue source and not a revenue generator.